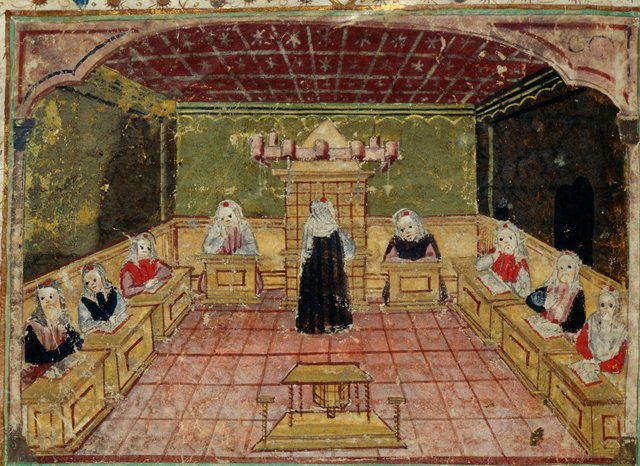

Artist – probably Giorgio d’Alemagna British Library, Harley 5686, f. 28

No kiddush. No kibitzing. Who wants to go to shul?

While large synagogue buildings lay fallow in much of the Jewish world, there was a shtender [book holder] hanging off a tree in a popular road in the heart of Golders Green. Here, the men gathered to pray and drop a few coins of charity into the pushke box that had been taped to the tree. Then, as London’s Orthodox synagogues began to re-open, corona-compliant guidelines were issued: a limited number of worshippers, no singing, the wearing of masks, a shorter service and social distancing. And therein lies the rub.

Shul without socialising is not a sustainable business model, and the regulars are not rushing to return. Pivot has been the buzzword of the corona era – restaurants doing take-away, manufacturers rejigging to produce PPE and synagogues becoming interactive TV stations, offering zoom prayer services and lectures on-line, while ramping up the welfare services for its isolated and elderly members. However, as shuls started to re-open, the fissures that run deep within the community have been exposed. Reform synagogues are shut – they deploy technological solutions on Shabbat and will meet on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur via Zoom. Masorti UK communities will produce materials for prayer and reflection at home, and online services and study sessions will take place before Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Where possible, some communities may meet in person.

In the Haredi communities, many home gardens and car parks became socially distanced sacred spaces well before shuls were allowed to re-open. From the action on the street, Haredi ritual life in Golders Green has been re-established, albeit with some tweaks. It seems women are less concerned with synagogue attendance, and no doubt some men were secretly relieved that they could not go to shul at the crack of dawn. But it was crucial to quickly re-establish communal prayer as the strong sense of male identity forged by minyan participation is key to consolidating the community’s social expectations and hierarchies. [I imagine there’s already a PhD proposal brewing that focuses on the gendered response to COVID-19 in the Haredi community.]

Perhaps the greatest challenge has been to the centrist Orthodox community in the UK, under the aegis of the United Synagogue – an umbrella body of 62 synagogue communities that ‘is committed to Judaism that is a continuation of the normative orthodox halachic process.’ Although Orthodox in name, the reality is that many people who attend their synagogues, even those who come fairly regularly, are not themselves particular about Shabbat observance and or keeping kosher. This is also its strength as the membership is diverse and there is a commendable emphasis on creating community, encouraging life-cycle celebrations, providing welfare support and offering educational programs. In addition to Zoom prayers on weekdays, communities across the UK have excelled in providing online social activities and welfare support during the pandemic, and rabbis and lay leaders are thoughtfully reviewing the potential options for in-person services during Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur.

While there is much to appreciate about the United Synagogue, COVID-19 has exposed centrist Anglo-Jewry as largely Orthosocial – an events service, catering to the lowest common denominator. I fear that this unwitting celebration of the Orthosocial augurs the demise of an intellectually engaged, halachically observant centrist Orthodoxy in the UK, a lifestyle that is, in any event, hanging on by its fingernails. And let’s consider that the frum-signalling characterizing some charedi behaviour also masks Orthosocial practice. Orthosocial is a phrase I’ve coined as the next iteration of the term ‘social orthodoxy’ so eloquently discussed by Jay P. Lefkowitz a few years ago in his essay, The Rise of Social Orthodoxy: A Personal Account. Reflecting on life in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, he writes

Unless one were to look very carefully, I would appear to be the very model of an Orthodox Jew, albeit a modern one. But I also pick and choose from the menu of Jewish rituals without fear of divine retribution. I root my identity much more in Jewish culture, history, and nationality than in faith and commandments. I am a Social Orthodox Jew, and I am not alone. He also acknowledges, because religious practice is an essential component of Jewish continuity, Social Orthodox Jews are observant – and not because they are trembling before God.

Orthosocial is a construct to satisfice the demands of ritual life, and during COVID-19, its ubiquity has only been heightened. However, although it’s a legitimate means of expressing one’s connection to the Jewish community, can it be defended as sustainable or optimal? We know that many of the adult children from the more observant families in the United Synagogue have made, or are considering making aliyah, while others have shifted allegiances to the Haredi or Haredi-lite communities. A small number have opted out and created opportunities for more inclusive Orthodox engagement via partnership minyanim and a small number are active in their local United Synagogue, breathing new life into ageing communities. However, more common are the swathes who have simply drifted further away – Jewishly illiterate, disillusioned and disinterested. An Orthosocial policy is not effective as the United Synagogue has limited sway over these young people and they remain unaffiliated during their formative young adult lives. Eventually, some may re-join and pay their fees in order to get married, have their children attend a Jewish school or be buried in an award -winning cemetery. It is in effect, the shul that they don’t go to.

Lured by the promise of a shorter service, and a nod to the nostalgia of the shofar sounds, there might be a temporary surge in synagogue attendance during this Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. However, the rabbis are going to have to work hard to entice their flock back to shul after the pandemic. Recidivism is low: there’s no Shulgoers Anonymous for those withdrawing from shul attendance – it’s a habit that seems pretty easy to give up. The challenge is clear: shul buildings will need to be repurposed and ritual life rebooted. No-one wants to go back to a Shabbat morning 3-hour prayer service, even if the gossip is salacious and the herring and whiskey are first-rate.

First published 28th August, 2020