I’ve made a cake for Sarah Schenirer’s birthday. Just a simple one. She would have been 136 years old today. And I shall drink a l’chaim in her honour. The self-effacing type, she would have blushed at the thought of big fuss or rowdy birthday bash. As she writes in her diary, By the time I was 6 years old I had a nickname in school, ‘Little Miss Hasid.’…They used to say that the whole house could be burgled in front of me and I wouldn’t notice, so engrossed was I in the pleasures of reading Jewish texts.

Sarah Schenirer changed Jewish life in the 20th century. The global and extensive network of Bais Yaakov schools owe their existence to this pious pioneer, and yet the complexity of her life and the challenges she faced are often sidestepped in favour of the hagiographical narrative of the ‘simple seamstress’ who inspired eminent rabbis to provide an education for young Orthodox women.

I think of Sarah Schenirer as a scholar-activist and her activism was contemporaneous with two other scholar-activists deserving unfettered admiration, Henrietta Szold and Bertha Pappenheim. They were all extraordinary, which means, as Szold wrote, to rise above human feeling. It means to be intensely human, it means to raise ordinary feelings to an extraordinary plane.’These three women were intensely human, willing to go beyond the boundaries, breach acceptable limits and forgo the earthly delights of a conventional marriage and motherhood. [Schenirer was briefly married twice, but the other two never married and none had children.]

These three women have had scholarly articles and books dedicated to their work, and Szold and Pappenheim have even merited their own stamp. However, it is Sarah Schenirer who seems to be ‘hot property’ at the moment, and I’ve been trying to work out why. In a thought-provoking new book, Naomi Seidman, highlights how competing forces such as Zionism, feminism and secularism contributed to the evolution of the Bais Yaakov system. The book also includes the first English translations of Sarah Schenirer’s writings in Yiddish and in Polish and a complementary website provides fascinating archival material.

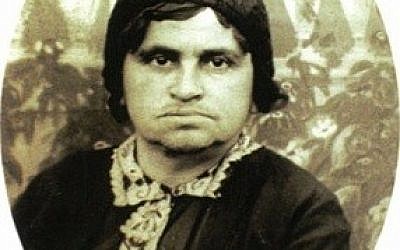

Sarah Schenirer, Passport Photo. (Wikimedia Commons)

Two issues raised in Seidman’s book may offer some clues as to Sarah Schenirer’s current popularity. The first is the economic driver. As Seidman notes, Sarah Schenirer’s revolution not only expanded the educational options for Orthodox girls, it also created a cohort of educated, mobile, committed and independent Orthodox young women, giving them unprecedented opportunities to combine religious commitment and socio-economic freedom.

In all the current deliberations about Orthodox women rabbis, one question remains unasked — could financial insecurity be driving the opposition to Orthodox women rabbis? The fact is that these new programmes preparing women to become Orthodox clergy are an economic threat to the livelihood of male rabbis, particularly male rabbinical students. These new women rabbis will also be looking for paid employment, thus expanding the pool of applicants for a job usually reserved just for men. Therefore, a qualified male rabbi will be competing with a qualified woman, and the very idea that a male rabbi could be overlooked in favour of employing a woman may provoke more ire than any halachic concerns. I wonder: with more women in this job market, is it conceivable that the number of men pursuing rabbinic qualifications in the modern Orthodox sector will decrease significantly? Will communities who will not hire women continue to rely on rabbis from the haredi sector to serve them? While an expansive view of the rabbi’s role includes their pastoral and educational responsibilities, the concerns about emerging women clergy may also help explain why some Orthodox authorities are narrowing the definition of a rabbi’s duties to those sacred spaces where it is largely accepted, even by Orthodox women rabbis, that only a man can perform certain Jewish rituals.

The second issue is the ongoing fear of feminism. Seidman explains that the most fraught relationship Bais Yaakov had with the sociologies of the time was with Jewish feminism. That it was a women’s movement was clear to all, and those of the left who associated such movements with the battle for women’s equality and rights celebrated it for that reason… However, when it suited them, Bais Yaakov strategically forged connections with women’s organizations and activists far beyond Orthodox or even Jewish circles, taking advantage of the well-publicised struggle against the international white slave trade to raise funds in western Europe and the United States.

Feminism has inspired the exponential growth of Orthodox women’s activism over the last 20 years and has contributed to the public discourse about women’s status in religious life. Organisations such as the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, Kolech, the Israeli Orthodox Feminist Association and Mavoi Satum supporting agunot have mostly existed since the late 1980s/early 1990s, but in recent years, social media has enabled them to engage broader audiences and galvanise interested parties to advocate on particular issues, including child abuse and domestic violence. Chochmat Nashim, an organisation that targets the increasing erasing of women from publications, is a relative newcomer to the activist field, and focuses on issues emerging emerged out of the obsession with modesty in the Orthodox community.

The Second Graduating Class of the Bais-Yaakov in Lodz, Poland, 1934. Jewish Women’s Archive

However, it appears that in the educational sphere, feminism is still a dirty word, and many of the leading institutions that are revolutionizing Orthodox women’s education in the 21st century do not use the word feminism in any of their promotional material. Schools offering women advanced Talmud to enable them to render decisions, or programmes to promote women’s communal and religious leadership seem reticent to acknowledge the impact of the wider feminist movement, even though they are engaged in a feminist act: disrupting a system that relies on keeping knowledge and decision making in the hands of men. An alternative explanation is that the women and men who founded these institutions have no need to articulate any feminist credentials for the mere act of supporting women to learn Talmud and enable them to become autonomous decision makers is more subversive and transformative than any feminist rhetoric.

Orthodox women are at the forefront of change in the Jewish world. It might be convenient to dismiss their increased ritual participation and emerging religious leadership roles as mere faddism, but that would be naïve and short-sighted.

I’d suggest that if there’s a lesson to be learnt from Sarah Schenirer’s life, it is that changes and opportunities in the lives of Orthodox women impact the whole Jewish world. For example, thousands of Bais Yaakov graduates are not all confined to the relative insularity of their community. While they shape large swathes of Jewish life within the Orthodox world, they are also having an impact as teachers and communal workers outside their own communities. So too, the modern Orthodox women who are deeply engaged in textual study, intending to dedicate their lives to the future of whole Jewish community.

Economics and feminism are converging in the growing cadre of educated, financially independent Orthodox women, who are using their power to leverage funds to support initiatives that are creating change and influencing social policies in the Jewish world.